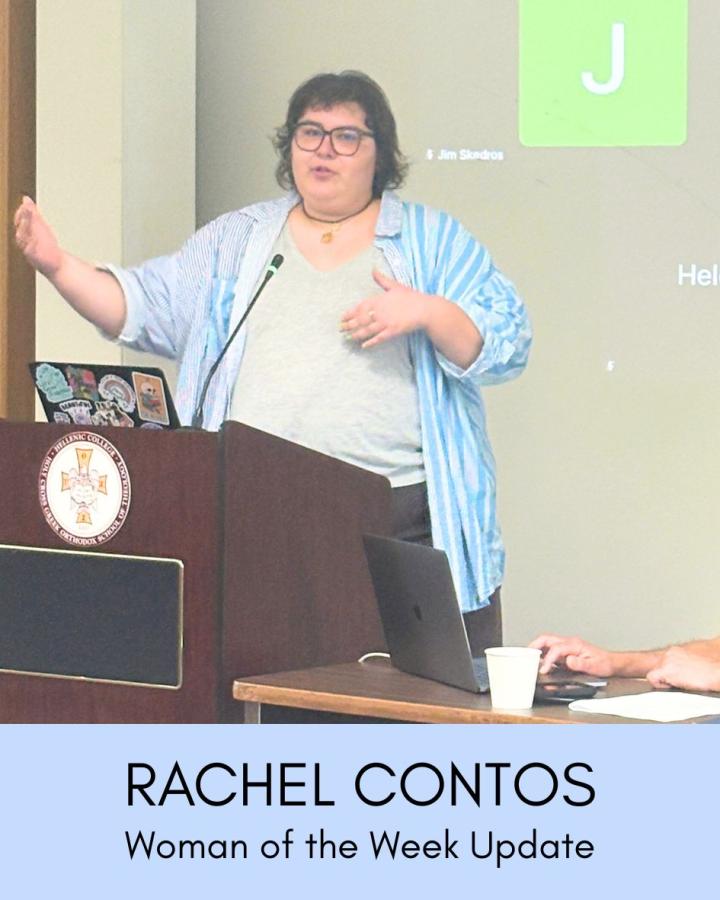

Rachel Contos was a Woman of the Week in 2021. She was originally featured for her work in community organizing around ending homelessness and improving maternal and child health. Her experiences in community organizing helped determine her graduate studies, and she has now finished the coursework for her doctoral studies and is on the verge of writing her dissertation in religious ethics. She recently presented a paper at the Orthodox Theological Society in America, representing our organization, and we asked her to share it with you.. It is called, “Axia Women: The Experience of Women in Church Life.”

“For today’s talk I’m representing Axia women as a board member. For those of you who may be unfamiliar with Axia Women, we are an organization by, for, and about Orthodox women in the service of Christ. Our vision is to be an organization where women are dedicated to lifting up one another’s gifts for our own salvation and the well-being of the whole Church. Axia is cross-jurisdictional and includes members from both the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Churches. Axia was asked by OTSA to present on women’s experience in the Church.

“An important caveat before I begin– this will not be a declaration on women in the Church, as such a universalizing statement would be impossible and frankly, irresponsible. Axia also found through our six years of work and all of our surveys that women are not a monolith!! We don’t all want the same things – survey results don’t always agree, we don’t always agree as an organization, and we certainly don’t assume that understanding women as some “essential” existence is possible or even preferable.

“With this said, I will be sharing data from our comprehensive survey of women across the Orthodox Church– both Oriental and Eastern– and their experience of Orthodoxy. Alongside this aggregate data, I will share stories of Women of the Week and other Axia women who have agreed to have parts of their experience shared. My hope is to paint a picture of the complexities of life as an Orthodox woman in a patriarchal Church– the joy, the sorrow, the moments of hope, and the moments of hurt– and, of course, possibilities for the future.

“First– why Axia Women?: “Axia was founded in 2019 after a survey of about 200 Orthodox women leaders in the Church showed that one of the most important ministries they needed was a space to be with other women across jurisdictional lines, ethnic lines, and geography. Women in high levels of leadership in the Church were isolated, lacked training, and their work went unacknowledged.

“The survey found that there was an incongruence between what we knew about Orthodox women in parishes– they led parish councils, they baked prosphora, they led the choir or chanted, priests' wives did ministries, etc– and what we saw:

“Images of women surrounded by men on the solea standing statically; pictures of women getting blessings from men; pictures and videos of liturgy without any women present.

“Axia’s very first program was the Women of the Week series where we highlight one Orthodox woman each week and highlight their work in the Church. People thought there wouldn’t be enough women to last a whole year– and now after six, we have a backlog of WoWs. We’ve featured the stories of academics, of chaplains, chanters and church musicians, activists, missionaries, archivists, and artists just to name a few. Women whose work makes the Church fuller and more beautiful– women who are part of the uplifting of the Body of Christ.

“Axia was founded on the idea that women’s activities, experience, and lives in the Church mattered; that creating support, training, and healing networks for women was worthwhile; and that when Orthodox women get together, amazing things happen.

“Women’s experience: With the foundations of Axia in mind, let’s turn to some of what we have learned about women’s experiences in the Orthodox Church. First, I will explore women’s participation and bifurcation; next I will shed light on the simultaneous hypervisibility and hyper invisibility of women; and lastly I will reflect on some ways that women’s experience is a mirror to the ways Orthodoxy isn’t living up to its own theology.

- Participation and bifurcation

“Women are often able to participate in parish life in ways that are joyous and sometimes fulfilling. One woman noted in our most recent survey from last year

“Women are involved in every aspect in the life of our parish from Parish Council president, editing the newsletter, overseeing social media accounts and email for the church, church school, choir, handmaidens for girls, cleaning.”

“At the same time, there is often a bifurcation to this joyous participation. This bifurcation can look like a difference between men and women doing the same role. One woman noted that in her parish:

“Women act as readers, but are not given the title of reader (although men are). Women readers are not allowed into the altar to receive the blessing before reading, although men are.

“Sometimes the bifurcation is within the self. For example, one woman who had been quite high-powered in her career and highly organized said the following:

“Our parish is happy for women to do as much unpaid work as they are willing to do, but--because they aren't paid--the priest and other council members have no qualms about making the work difficult. …There's also little sense of the value of women's work. For example, our prosphora-making team baked 180 loaves of prosphora to prepare for a period during which we wouldn't have access to our industrial-sized kitchen. Our priest gave away 150 of those loaves as a favor to a local mission--without asking them what that would mean for their plans. There's just a sense of entitlement to women's unpaid labor...

“So women were involved in the joyous activity and asked to participate in their parish life in order to prepare the parish for a time of change and transition– and then at the same time completely ignored. They were bifurcated; not seen as bakers and project managers overseeing a Church transition, but the ladies who just did a nice thing.

“Many women shared that they cannot be “strong” or outgoing in Church. Women who are allowed to be themselves in the world in some ways that are meaningful cannot bring these aspects of themselves into their parish life where they would like to bring her full self. Women said the following:

“‘Our diocese as a whole does not support women in leadership positions or women teaching, other than children’s groups. Women definitely still have a “place” and it is usually quiet and at the back.

“‘I think the biggest problem at this parish is an unconscious attitude from our priest towards strong women. And we have had no dean or bishop willing to consider even facilitating a conversation about it. I don’t think they see it or believe it. But I have watched many women leave and have nearly left several times myself. If we had options, I expect we would have left.

“It is difficult to believe in the fullness of the Church when the self is split and bifurcated in what is supposed to be our home, our apprenticeship, our hospital. We ask women to be present in the Church, in our liturgies, in our organizing of parish life– but not as their whole selves, as the bifurcated self. How can women heal, love, find joy when we can only participate as partial, often caricatured versions of ourselves?

2. Hyper(in)visibility

“Orthodox women’s experience in the Church can be described as one of being both hyper invisible and hyper visible at the same time. Jeannine A Gaily argues in her article “Undesirably Different” that “human bodies exist on a spectrum of visibility, from hypervisibility at one extreme to invisibility at the other. We are all visible and invisible at times, but it’s how visibility and invisibility function that is both a consequence of social hierarchy and simultaneously reinforces that same hierarchy” (20). She goes on to define hyper(in)visbility as “the phenomenon whereby marginalized bodies are subjected to both an extraordinary amount of attention and scrutiny and are simultaneously completely disregarded and dismissed.”

“Orthodox women experience hyper invisibility and hyper visibility in the Church often. For example, one woman noted:

“‘I wasn't really prepared for the fact that the decision to hire a woman in my role would be controversial. I do have a handful of allies who respect my professional background as an educator, and who seek my insights. But I'll admit it's been really lonely and frustrating to operate in a system that I believe is often sexist. I think what's most frustrating and hurtful to me is how some parishioners and staff have loads of patience for our Priest and lead cantor (both male) while they feel very free express their judgments and criticisms of my work, even when they have not taken the time to fully understand the nature of my goals and projects. In staff and parish council meetings, I spend loads of energy marketing myself and selling my ideas.

“You can hear in this quote the simultaneous need to sell her position and ideas, trying to gain visibility; while also being overly scrutinized, seeking some form of grace in the form of invisibility.

“One woman shared a story of getting invited to a dinner with Patriarch Batholomew at the Fanar in her role as an executive director of an Orthodox organization. The staff at the Fanar had not realized that she was a woman and had assumed the ED would be a man. As such, she had to sit in the basement during dinner. The next day while she waited for the Patriarch to arrive for her meeting, she crossed her legs at the ankle and a deacon touched her knee to tell her to uncross it. Imagine being so visible to the male gaze at the idea of even being in a dining room as a woman that you have to be rendered invisible. Imagine your legs crossing being simultaneously so scandalous as to be all one might be able to fixate on while being so invisible as to not have the reality of touching your knee be perceived as inappropriate.

“Hyper(in)visibility, as Gaily notes, is a key to the process of othering. Many women expressed feeling unseen, like their priests and other men in parish leadership did not have the desire to be culturally competent around women’s issues. Their needs and embodied realities are seen as unworthy of being noticed. At the same time, women shared stories of having a bra strap tucked into their shirt by a man; being yelled at by a priest for changing into sweatpants mid-liturgy because they had bled through their skirt during a particularly heavy period, chased down the aisle of the church with a headscarf in hand to be put on their head.

“Another example that I HAVE to share because I honestly think it’s hilarious, has to do with how we recruit Women of the Week. Almost all of them are recruited by other women who see them. Conversely, when we approached bishops to write blogs about influential women in their lives, we had to tell them the caveat that it couldn’t be the Theotokos or their own mother. We never did that blog series.

3. Living up to the Church’s own theology

In Carrie Fredrick Frost’s book “Church of Our Granddaughters”, she argues that “Oppressive structures of the Orthodox Church are oppressive in relation to Orthodox doctrine.” Women’s experiences in the Church can act as a mirror to the ways we are not living up to our own theological standards. Women often KNOW the theology and feel in their bodies that it isn’t happening. They don’t want to leave or even want huge change often. They want simple things, like being seen as a full human person. One woman said this well in our survey, noting:

'There is no… - "no male or female in Christ" - but the Tradition is so male-centric in terms of worship, etc., it's not hard to see how some women may feel completely like 2nd class citizens.’

“Women also understand that there is a clear theology that encourages women’s ordination to the diaconate. Women also understand that anyone can go behind the altar screen with a reason, but it is men who somehow always make reasons for men to enter the sanctuary and not women. As some respondents said:

“‘Allow women to become Deaconesses - allow them to read the epistle and hold the communion cloth during serving. Allowing them to serve as ushers. LISTEN proactively to get a real sense of what women are thinking and feeling about their role in parish life.’

“‘Women deacons and priests make sense to me and the Orthodox Church has taken a back seat in instituting this important early church tradition. ‘

“‘I think it would be good if our handmaidens could go into the sanctuary during services. Actively support the reestablishment of female deacons.’

“As a Church we write beautiful theology of theosis and liturgy; we have a loving theology of the Body of Christ. We understand ALL people as co-working together toward communion with God. We acknowledge that the body matters in our sacramental and liturgical theology. And we see in surveys that when women CAN do the aforementioned activities, they are filled with joy.

“And yet– women’s experience acts as a mirror to the ways we deny the body, the ways we denigrate parts of the body of Christ, the ways we make participation in the liturgy and sacraments more difficult or sometimes push women to excommunicate themselves. Taking women’s experience seriously can help us right the ship and live up to our own standards.

“Something I’ll never forget was someone in a meeting Axia was having said that they hadn’t been going to Church because of a traumatic experience and they felt like Axia was Church for them. A board member at the time pushed back saying, “you need to be on the vine” and asked “what can we do to make you on the vine?”

“What that person said wasn’t “No, you didn’t feel pain.” Instead, she disagreed with HOW it was dealt with, she didn’t deny that the pain was real. When we in the Church have disagreements about women’s involvement, these disagreements shouldn’t involve discounting experience, but should instead ask the best ways to account for these experiences.

“Axia asks that question- how can we grow the vine toward you– every day for women because we do not want to replace the Church; we want to ensure that women feel they can continue to be on the vine as their whole selves, seen for WHO they are and not as a what, and within a Church that lives up to its own beautiful theology.”

Thank you, Rachel!