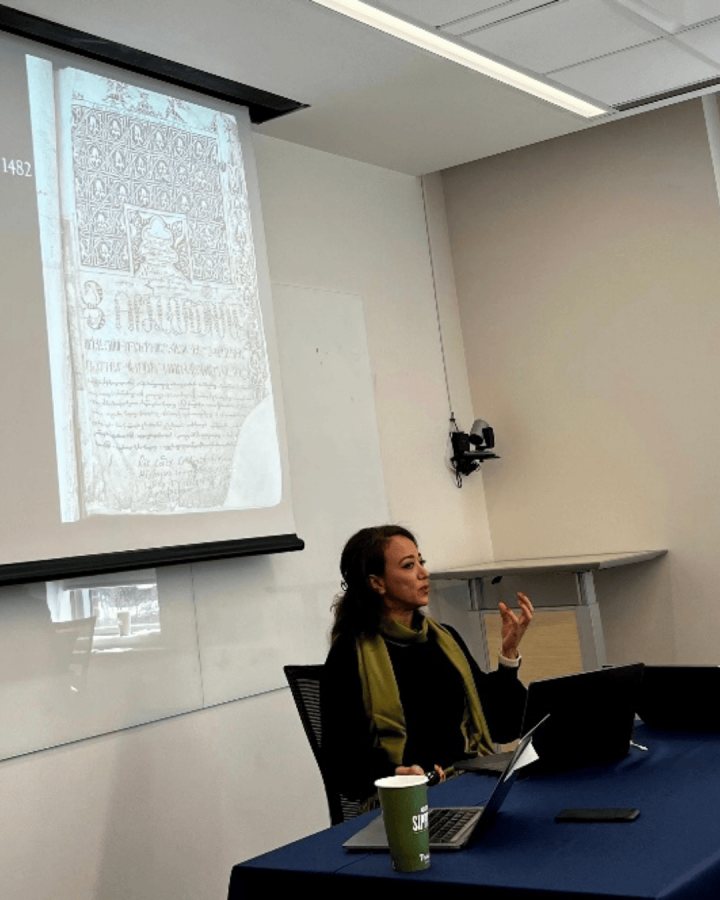

Ani Shahinian is our Woman of the Week, nominated for her role as Assistant Professor in Armenian Christian Art and Culture at St. Nersess Armenian Seminary and St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary. You see her here teaching her class "Biblical Exegesis in Text and Image" at the MET, and researching Armenian Christian Monasteries in Lake Van, Turkey. We asked her to tell you how she got from where she started to where she is today:

“It’s been a long journey. I’ve made multiple turns—it wasn’t a straight path. Not in the spiritual or professional sense. God does make our path straight, you know, but there were turns left and right.

“I started out wanting to be a constitutional lawyer because of the injustices in my family. Many family members—especially women—were voiceless, whether through marriage, parental relationships, or their underprivileged communities. I cared deeply about justice, truth, and righteousness, and I believed becoming a lawyer would allow me to be a voice for the voiceless.

“As a young girl—five, six, seven years old—growing up in Hollywood, I was always alert to injustice. The stories from my family, shaped by grievous experiences—not only the Armenian genocide, but malpractice and other injustices afterward—settled deeply into my conscience. They informed what I felt I was meant or called to do as a child of this legacy.

“So law became my passion. I studied philosophy as an undergraduate and went to Washington, D.C. before law school. Before I even turned 21, I had the opportunity to work at the White House,the Supreme Court, and the Justice Department. That experience ultimately led me not to go to law school. I ended up working at the Department of Justice, and toward the end of my time there I was assisting in investigating and prosecuting human trafficking cases. I worked closely with traumatized women and walked with them as they entered victim-witness programs. It was difficult and meaningful work.

“Around 2009, something shifted in me. I began to feel that while many people could do what I was doing, there was something I was meant to do that no one else could. I couldn’t yet name it, but I felt an inner pull. At the same time, I became involved with the C.S. Lewis Institute—first as a mentee, then as a mentor—in a rigorous discipleship program focused on formation, study, and spiritual practice.

“During the day, I worked at the Justice Department; in the evenings I studied theology and philosophy, asking and seeking what it means to follow Christ. In 2009, I visited Jerusalem and Armenia for the first time and felt strongly that my Armenian Christian heritage—my family’s history—was calling me toward something new. Still, it would take a divine encounter to make the transition.

“In 2013, I received partial funding to study theology at Oxford. Leaving my career was a huge leap of faith. Within the first few months, I realized Oxford was not my long-term destination, but I met with future supervisors and finally voiced the question that had been burning in me: What does the Armenian Church say about martyrdom and Christian witness? What has been studied about Armenian Christian martyrs?

“They told me no one had really looked at it and asked if I would be willing to study it. That moment—now twelve years ago—became a small seed that grew into further degrees and eventually my doctoral work at Oxford.

“Through that work, connections formed. I reached out to Dr. Roberta Ervine, and in 2019 I visited St. Nersess midway through my doctorate. In 2022, after defending my dissertation, I was invited to teach an intensive course on Armenian Christian martyrdom. A few months later, a funded faculty position opened, allowing me to join the seminary on a more permanent basis.

“The timing was exact. A year earlier or later, it wouldn’t have worked. Throughout all of this, there has been a recurring question in my heart from Christ to me: “Do you trust me?” And I answer, “Yes—I trust you, but…” And then, when things unfold, I’m reminded how much I want to trust fully. I wish I could be faithful and trusting without the “but…”.

“Now I’m in another season where that question has returned. And looking back over twenty-five years, I can say: I do trust you. I don’t know what will happen, or whether it will look like what I once imagined. But based on these years, based on my family’s history and the generations before me, I know this much—Christ has been faithful, always!.”

“I am currently working on the book version of my doctoral thesis. In one sentence, what I often share about Armenian Christian martyrdom—historically and theologically—is this: from the seventh century onward, for nearly 1,400 years, Armenian Christian martyrdom has taken the form of resistance. It is a tenacious conviction that when all else fails—even the defense of faith through words—actions themselves become the illuminative, virtuous force that bears divine truth. It is a witness for Christ, particularly to the Muslims of their time, because sometimes words fall short. As we often say, actions speak louder than words.

“There is an earlier period, in the first few centuries, where this dynamic is not directly applicable, though it remains relevant in light of pre-Islamic contexts. What I found myself returning to again and again—especially in choosing to focus on a very narrow period in the fourteenth century—was that this was an interregnum, a moment of major power players coming and going. It was a space marked by hemispheric, regional, and local power contentions. In many ways, it was a worst-case scenario: things were terrible. And yet, it is precisely there that the light of the martyr shines.

“That light speaks of divine virtues of hope, love, and faith—embodied by both men and women. There are many women martyrs in this period whom I deeply admire. In fact, the very first text I read with Dr. Ervine when I came to St. Nersess in 2019 was about T’amar Mok’ats’i, who was martyred on April 22,1398. I was working on the publication of that article here at the seminary at the time.

“This was a moment in history marked by a collective cloud of witnesses (Hebrews 12:1)—a large group of martyrs over roughly fifty years who stood firm and resisted the imposition of another’s will. They did so through their own agency, responding to what they understood as Christ’s call on their lives. It is an extraordinarily powerful and meaning-making period, and I did not arrive at it quickly. Like the work itself, this understanding unfolded as a journey.

“The story of T‘amar is the following. T’amar Mok’ats’i,was married to a Christian man and had two sons. One day, a Muslim Kurd in her village of Mok’ saw her and desired to take her as his wife. He devised a plan to kill her husband and take T’amar. She learned of this through the village grapevine the night before it was to happen. She informed her husband, and together they packed what they could and fled to the island of Aght’amar, which at that time served as a protected enclave for Christians. Aght’amar was a fully autonomous Armenian Christian community, a small island off the southeastern shores of Lake Van, facing the city of Vostan, modern-day Gevaş. They traveled through Vostan, crossed by port to the island, and lived there for five years under the protection of the Catholicos, Zak‘aria II of Aght‘amar. After five years, they visited the mainland for some necessities. Tamar was recognized by members of the Muslim community, who brought false charges against her, claiming that she had once converted to Islam and had now reverted to Christianity, hiding on Aght’amar to avoid charges of apostasy, according to Sharia law.

“We know from the account and other historical evidence that this was not true. She had never become Muslim, never married the man who pursued her, and had fled precisely to preserve her faith, family, and life. Nevertheless, the charge was that she had converted and then escaped. The judge initially handled her case but eventually handed it over to Pasha Khatun, the wife of the regional emir, to adjudicate. Here we encounter a striking moment: two women positioned within a struggle over law, will, and witness. T’amar’s narrative weaves together her testimony—her imprisonment, the attempts to force her conversion back to Islam, and ultimately her execution as an apostate in the eyes of the authorities.

“As we study the stories of the martyrs, it becomes essential to understand the historical realities that shaped them, and to ask what those histories prepare us for. When I left Washington, D.C., one phrase echoed constantly, especially around major events and powerful decision-makers in D.C.: “History repeats itself.” I found it frustratingly vague. What does that mean? Does it suggest an unwillingness to learn? A failure to attend to what has already happened? Is it simply a matter of ignorance? How do I contribute to all of this?

That question is part of why I consider myself a historical theologian, not only a theologian. For me, theology must be grounded in historical reality—how theological ideas developed, and how history itself shaped and was shaped by those ideas. Further, today my work brings Armenian Christian art into conversation with all of this. I bring the theology, the history, but I also bring visual culture to enrich our conversation on a given topic. Every lecture is enriched by Armenian Christian illuminations and artifacts—ways of seeing that go beyond text alone. The two courses I have developed thus far are Biblical Exegesis in Text and Image and Armenian Martyrs in Text and Image. Alongside the texts, we study illuminations of martyrdom scenes, icons, artifacts, architecture, and the broader traditions surrounding relics. This brings the learning full circle. We engage not only words, but objects, images, and beauty. I believe beauty is a trace of the divine woven into humanity. God creates beautifully; everything He does is beautiful. So why would we settle for learning—or living—only for function?

As always, we asked our Woman of the Week, Ani Shahinian, to tell you about her morning routine:

“Immediately, when I think about my morning routine, I think of two versions: the ideal version and the real version.

“I always say mornings start the night before. For me, mornings don’t really begin when I wake up; they begin with how I go to bed. It’s important for me to have a meditative mindset before resting, because sleep is what nourishes me for the day ahead. Ideally, I wind down, reflect, finish work, get off screens relatively early, and then engage in reading Scripture and devotionals that nourishes me before bed. I also like to journal right before going to sleep.

“The first thing I practice when I wake up is gratitude. Ideally, reflecting on Scripture instead of scrambling to get to the next thing. I meditate on the same Scripture in the morning that I read the night before because it is grounding for mind, spirit, and body.

“Fitness and movement is very important to me, but in the mornings it can be physically hard to get the joints going. Ideally, I combine meditation with stretching. I like bringing the spiritual and the physical together—heart, mind, soul, and strength—as Christ gives the golden commandment in Luke 10:27. If my mind is engaged, my body is stretched and aligned, and my heart is oriented properly, everything comes together, just like a piece of art.

“The reality is that doing all three becomes ideal when not practiced daily. Sometimes I skip the stretching, or my attitude of gratitude and then I’m more stiff and less flexible, and my day feels a bit slower than I’d like. One thing I do try to do each morning, though, is drink 12 to 16 ounces of water before going straight to coffee. My routine usually looks like this: water, meditation, devotion, more water, stretching, coffee, and reading—which is such a refreshing, emotional, spiritual, psychological start to the day.

“If I’m at the seminary, I like to participate in morning prayer. That often leads into a fifteen-minute walk, which is a really good rhythm to have.

“I think one thing I always encourage others is: Find older women to follow, find younger women to lead. This allows a healthy balance of being poured in but also pouring out into others. One thing that makes the spiritual life so rich is that we're not alone, first because Christ is with us and in us, but He is also with us in others."

Thank you, Ani!