In the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Christ is Risen!

May 16 was the Sunday of the Myrrhbearing Women in most of our Eastern churches. The Myrrhbearing Women weren’t a thing in the Reform tradition I grew up in. I first met them in an icon in a monastery in northern Greece. In the icon, they looked like they knew what they were doing, a group of women carrying jars towards a sepulchre set in some rocks. It wasn’t until much later that I began to realize how impossible their task must have been and how terrifying it must have been to attempt it.

Even though they had been Christ’s followers throughout his ministry in Galilee, most of them are known today only for what they did as Myrrhbearers. They stood by the cross, and accompanied him to his tomb, to find out where it was. Then, despite all the obstacles, they returned to it at the earliest possible moment to complete the burial rites.

So as a group the Myrrhbearing Women are symbols of enduring love and faith, but they were also people, each an individual in her own right. I’d like to spend a few minutes considering each of them. Each of them would have remained important members of the early Christian communities, which included their names in the Gospel accounts as credible witnesses.

Before we get to the Myrrhbearers who went to the tomb first thing on Resurrection morning, though, I’d like to break out Mary and Martha of Bethany, which was a small village in Judea near Jerusalem. They are identified as Myrrhbearers in the Orthodox tradition, even though none of the Gospel writers names them as being in the main group. Why then are they considered Myrrhbearing Women? I imagine it must be because they minister to Christ—not at the tomb, but at their house-- before he sets out to Jerusalem to meet his death.

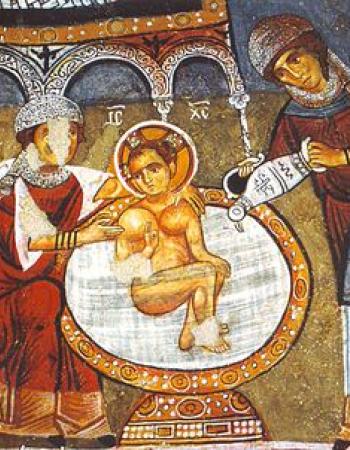

- So: Mary of Bethany. She was one of the sisters of Lazarus, whom Christ raised from the dead. She is the one who sat at Jesus’ feet listening to him teach. She apparently absorbed his teachings better than almost anyone else among his disciples. As a result, she seems to be the only person who truly understands who he is, what is about to happen to him, and what he needs—and so she anoints him—extravagantly. He realizes that she has, in effect, in advance of his death, performed the first part of a burial ritual.

(As a side note, the fact that she has a pound of pure nard—worth the equivalent of a year’s wages—suggests that she and her family were people of great means.)

Like any other big gesture, it caused controversy. Some people thought the ointment should have been sold to benefit the poor. Jesus agreed with Mary, not them.

- Martha of Bethany, her sister, tends to Jesus differently. Clearly she reveres him and wants to serve him properly. To her, that means as a hostess she needs to strive to keep the house and the food up to standard for their guests. Middle-eastern hospitality tends to be a big deal. At their first recorded meeting at their house, she wants obey the tradition in which she lives and is distressed when her sister doesn’t help. When Jesus says, “Martha, Martha” to her, what I hear is less a rebuke than a consolation. He’s honoring her intention and saying, “It’s ok! You don’t have to do all of those things! It’s ok to put everything aside. This crowd doesn’t need all that. I won’t judge you if you don’t do all that. It’s okay to just listen.” And later, when Mary is pouring nard over his feet, Martha herself is serving him at the table.

- Tradition has it that, after the martyrdom of St. Stephen, Lazarus was cast out of Jerusalem. Mary and Martha left Judea with him to spread the gospel. It is said that Lazarus became the first bishop of Kition, in Cyprus, where they are all three said to have died.

So Mary and Martha each try to take care of Jesus as best they know how, in advance of his death. This may also be why the Theotokos is considered a Myrrhbearer, though none of the Gospel writers names her as being at the tomb, though she was at the Crucifixion, when Christ assigned her to a new son, so that she became an adopted mother to the disciple whom he loved.

That brings us to the Myrrhbearing Women who want to care for Jesus AFTER his death and ARE named as going to his tomb. So, who were they? They were Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, Salome, Mary the mother of James and Joses, Joanna, and Susanna.

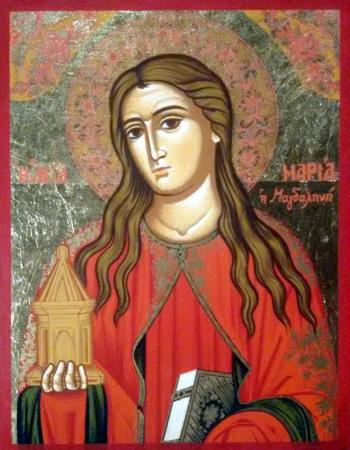

- Let’s start--like everyone else--with Mary Magdalene. She appears as a Myrrhbearer in in all four Gospel accounts. Little is known about her life, much less why she was called Magdalene. Most think it was because she came from the fishing town of Magdala on the Sea of Galilee. A few others conjecture it was because “magdala” in Aramaic means “tower” or “elevated, magnificent” and it was given to her because of her stature among the disciples and her degree of faith. She is always listed first in any group of women disciples. It has been suggested that she occupies the position among them that Peter does among his male followers.

She must also have had some wealth, because Luke says she was one of the women who helped support Jesus. He also says that Jesus had exorcised seven demons from her—a huge trauma--probably privately, because there’s no description of the event. She had reason to be grateful! After the crucifixion, tradition tells us that she followed the Evangelist John to Ephesus, where she died and is buried.

- The next Myrrhbearer to consider is Mary the wife of Clopas. To us today she is mysterious figure but, at the time, she would have been very well known. She was married to Clopas, also known as Cleopas, the brother of the Theotokos’ husband, Joseph. Mary of Clopas was therefore the Theotokos’ sister-in-law and Jesus’ aunt.

Mary and Clopas were probably disciples of Jesus who traveled with him from Galilee on his final journey to Jerusalem. After his Resurrection they became prominent members of the early Jewish Christian community in Palestine, where they—like others of Jesus’ relatives—actively spread the good news. Their son Symeon was one of the most famous and long-standing leaders of the early church in Jerusalem, until his martyrdom under the emperor Trajan.

- Another Mary is the mother of James and Joses and is sometimes called the wife of Alphaeus. She is mentioned as a Myrrhbearer in the Gospels of Mark and Luke. Jesus chose one of her sons, James, as an apostle. She is another woman who used her resources to minister to the Lord and his disciples. In fact, all we can really say is that she gave her income and her son to serve Christ, but those aren’t bad.

- This brings us to Salome, the mother of James and John who is mentioned as a Myrrhbearer in Mark and in Matthew. She was the wife of Zebedee, a fisherman prosperous enough to have hired servants. Salome appears to have become a disciple from the outset of Jesus’ public ministry. She is zealous enough that she asks Jesus whether her sons could sit at his right hand and his left hand in the Kingdom—a request that Christ immediately corrects out of compassion, not anger. Salome remained at the crucifixion even after her sons had fled. Her son James was the first of the apostles to be martyred, while her son John, who later wrote a Gospel and Revelation and adopted the Theotokos as his “mother”, was the last.

- Now we come to Joanna, the wife of Chuza, mentioned in Luke as a Myrrhbearer. She came from a wealthy Jewish family and had married the finance minister of Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee and Perea. So she moved in sophisticated circles, that also seem to have taken Jewish religious practices seriously. When Jesus became known as a healer, she sought him out to help her, and ended up becoming a disciple and supporter. After the Resurrection, she took up missionary work with her husband in Rome.

- The last of the Myrrhbearers is Susanna. We have virtually no biographical information about Susanna, other than that she became a disciple, like Joanna, after Jesus healed her. We can make some reasonable assumptions, however.

- Jesus’ women disciples—the Myrrhbearers among them--were his constant companions from an early stage of his ministry in Galilee. Their discipleship--like that of the men--consisted of accompanying him and witnessing his teachings and miracles.

Jesus and his followers lived without ordinary means of economic support and didn’t engage in economically productive work. They were too large a group to be able to depend on ordinary hospitality. So the women disciples—who were mostly financially independent--supplied their monetary needs. Any dependent family members they left behind would have been economically supported by male family members. The male disciples’ situation was a bit different. Any dependent family that they left behind would have had to manage economically without them, which can’t have been easy, so the men probably took almost nothing with them when they departed. Both the men who abandoned everything to follow Christ AND the women who gave their material resources for the common support of the community exemplify in different ways what Jesus taught about possessions.

So the Myrrhbearing Women, individually, were regional sophisticates or wealthy villagers, former demoniacs or invalids, ordinary householders, devoted sisters, mothers, aunts, or wives, Christ’s followers or his friends, bringers of myrrh to his tomb or nard for his feet in advance of his impending death. Whichever categories they may have occupied, they came together to to care for him in Christianity’s darkest moment.

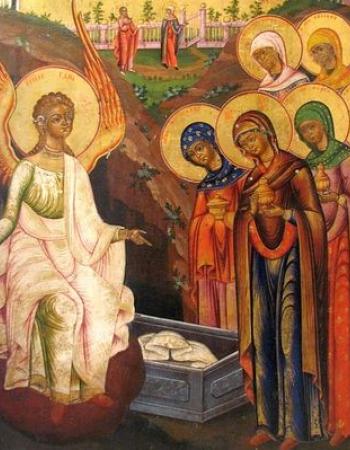

After virtually everyone else had fled in fear and grief because of the crucifixion, they decided to attempt the impossible--tend to Christ’s body. After all, a massive stone that they had no hope of shifting on their own sat in front of the entrance to the tomb. They had no hope of finding other disciples to help them, and they certainly couldn’t ask the soldiers who were guarding it.

But they gave each other courage, and hope, and fortitude. They knew someone had to do something. They came to the tomb even though he had been disgraced in the eyes of the Romans, the Jews, the whole of the known world. They came because he had loved them and taught them and done miracles for them.

They knew that, even though Joseph and Nicodemus had wrapped him with myrrh and aloes, his funeral rites—as dictated by Jewish custom--were incomplete. Had his eyes been closed? Had he been kissed with love? Had his body been properly washed? He had had no funeral procession, no women leading the way wailing or throwing dust on their hair. They came knowing his body was going to stink, because it had been more than eight hours since he had died. They came knowing that being in contact with his dead body would make them ritually unclean.

But because they acted in fear and humility, they discovered the Resurrection. They were the first to hear the good news. Can you imagine? And when the angel commissioned them to spread the word to the others, they became the Apostles to the Apostles.

May we too support each other in loving Christ and serving him past logic. Who knows where that will lead?

Patricia Fann Bouteneff is the founder of Axia Women. This is a version of sermon she gave at St. Gregory the Theologian at Union Theological Seminary in May.