From Holy Week 2020.

When I wrote my thesis for my MDiv degree at St. Vladimir’s I chose Holy Friday Vespers: the development of a new service and icon in the 11th-12th – 13th centuries. At this time of distancing during the Corona virus pandemic, I don’t know whether our churches will be open again, and whether we will be able to attend that most beautiful of Passion Liturgies. So, I decided to revisit my thesis and write a condensed blog about it.

The Christian faith has only one object: the mystery of Christ dead and risen. As a result, the Orthodox Church has structured time for the continual remembrance of this event. Pascha stands at the very center of importance in the yearly cycle of feasts; every Sunday commemorates Pascha/Easter as the focal point of the week, moreover, the focal point of every Eucharistic Liturgy is the sacrament of Christ’s sacrifice at Communion. It is the Resurrection joy of life defeating death that is central to the “Good News” shared by Orthodox Christians even to this day.

So, how did the moving icon of Christ, dead in His tomb, and the beautiful Passion services of the Entombment of Christ and His Funeral on Holy Friday develop? It was obviously a lengthy process: Jerusalem station services commemorating Christ’s Passion, moving from actual site to site, were adopted by monasteries of Byzantium as a way of mimicking Jerusalem, adjusting the rituals to work in their churches; from there, the secular churches of Constantinople imported the monastic rituals in order to, again, mimic the historic Passion Stations of Jerusalem. This development took several centuries.

From the late 9th to the 12th centuries there was a cultural hunger for more realistic stories about Jesus and the Theotokos. As a result, both iconography and hymnography reflected this desire for greater human emotion and pathos. At the same time, after Iconoclasm, there was great surge of creativity in liturgical poetry and iconography, in a way, making up for lost time. There was a tendency, with the increasing humanism, to make the drama of grief very real.

A nun from Spain named Egeria (4th C) and other later pilgrims wrote about their experiences in Jerusalem during Passion week and Pascha. After a while, all throughout Byzantium churches began to mimic actually being in Jerusalem and the holy experience of taking down the body of Jesus from the Cross and laying it in a tomb. Historically, the first such copying is reflected in the service of the 12 Gospel readings on Holy Thursday as a version of the Stational services on-site in Jerusalem.

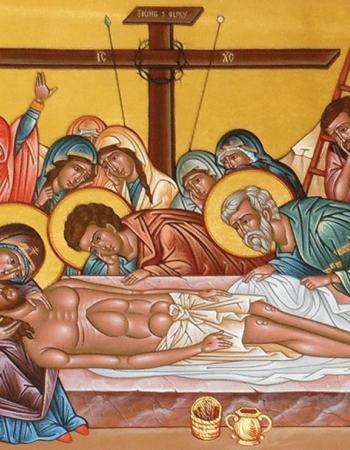

In many respects, the church services were the theater of the day. At first there were lengthy, very dramatic sermons about the grief of the Theotokos at the suffering and death of her Son. There was even a Passion play in Cyprus, whereupon, the wording of certain later hymns is directly taken from this play: “Give me that stranger and good man, which the Jews for envy have taken away to crucify.” (The Cyprus Passion Cycle) Iconography showing the whole cycle of the Passion developed across all of Orthodoxy: The Crucifixion, Joseph and Nikodemus taking Jesus’ body down from the cross, the figures of Mary Magdalene, the Theotokos, St. John, and Joseph and Nikodemus in grieving stance around the prone body of Christ. The rhetorical language of gestures, familiar to the public of the middle ages, is still pictured in contemporary Passion Icons today.

At the same time, iconography developing within Liturgy, centered upon the offering of the Gifts at Eucharist. All such iconography was focused on making obvious and literal the human death of Jesus Christ, and His presence in the offering of the Bread and Wine. In fact, it is the Great Entrance that is the source of the Epitaphion/Shroud as liturgical object. The Entombment Iconography –the shroud wrapping Christ’s visible body became a concrete sign of His death in contrast to the iconography of the” Women at the Empty Tomb” (showing the linen shroud and napkin left behind as symbols of the Resurrection). The symbolism of liturgical objects reflects the centrality of Christ’s death and resurrection. For example, the altar table has always been linked to the tomb. Originally the Altar Table was covered with a cloth called the ‘eleiton’ (in remembrance of the Shroud). But later the Antimension took over the shroud connection from the ‘eleiton.’ This Antimension was used as a portable altar and had a painted image of Christ’s body lying in the tomb. That is true to this day. With greater reference to Christ’s sacrifice, the entombment of the Lord was carried out in the Liturgy with ever greater symbolic detail. Eventually, by the 14th C. the cloth covering the Chalice and Discos, the ‘Aer’ became symbolically the Shroud, as was the under-vestment of the altar table called Shroud. Finally, the Great Entrance ritual at Hagia Sophia was described thus: “following the Gifts are those who bear a covering on their heads with an image of the naked and dead body of Christ.” (Symeon of Thessalonike.) From that time on, the “archeological and iconographic development of the appearance of ‘Aer/shrouds’ (epitaphioi) began their rapid evolution according to liturgical use.” (Robert Taft) That is also why the Epitaphion/Shroud is always depicted on cloth (as was the original shroud, linen cloth).

It is almost impossible to date the development of the Epitaphion Services very accurately, but allusions to it appear as early as the 11th-12th centuries. Finally, by the 13th Century, a period of synthesis, during which many local practices were coalesced, canonical church ritual finally emerged. Mention of them is made in the Cyprus Cycle and in the letters of Patriarch Athanasius, inviting the populace of Constantinople and the emperor to come to this wonderful new service of Christ’s entombment (13th C.) The parallel development of iconography and liturgy became the very affecting Vespers of Holy Friday, the Entombment of Jesus Christ.

There are hundreds of “Shrouds” today in the world. Some are embroidered on cloth, others painted, but all are central to the Holy Friday services in Orthodox Churches and are deeply loved and venerated. The Epitaphion, (Holy Shroud, Winding Sheet, Plaschanitsa) is seen as the central icon of the Orthodox Christian faith. This paradoxical image is of a horizontal, nude, full body portrait of the dead Jesus Christ, portrayed on a textile. As such, it is the complete opposite of the icon of Christ Pantocrator, the divine and majestic ruler, depicted overhead in the central nave. Although seen as opposite, this Christ is the same One who rules from above. ‘This’ One who rests in death as a man upon the tomb is manifested by the language of the service to be the same One as the Pantocrator, the Word of God and Judge who is to come.

The second very powerful theme brought to the attention of the faithful during Holy Friday Vespers is the image of death. The Epitaphion confronts the faithful with the reality of death, both Christ’s personal death and the ‘universal’ death which all human must undergo. None of us has witnessed a crucifixion. Horrible as its descriptions are, we have never experienced it first-hand. Death, however, we all know. All have lost loved ones; all mourn their loss. This is the living remembrance within us that makes this service so particularly wrenching. The presentation of Christ dead, brings forth a personal response of grief: “we are brought to venerate him who had such compassion for us, who saved us, at so great a price: to entrust our souls to him, to dedicate our lives to him, enkindle in our hearts the flame of his love.” (Nicholas Cabasilas, as quoted by Robert Taft). Emotionally this prepares us for the joy of the Resurrection. Without the darkness, who would exclaim at the light? Without the grief, how could there be the great Paschal rejoicing of midnight’s singing and holy cries: “Christ is Risen! Truly He is Risen!”

Tanya Penkrat holds a master's degree from St. Vladimir's Seminary.