Friday, October 22, 2021

This month we celebrated the Seventh Ecumenical Council, which was held in Nicea, Asia Minor, in 787. Under Empress Irene, 367 Bishops were present. The Council published a statement approving the creation and veneration of icons as an essential part of prayer, a way to encounter and experience the holy presence. The statement says, “The icons of our Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ, that of our Lady the Theotokos, those of the venerable angels and those of all saintly people. Whenever these representations are contemplated, they will cause those who look at them to commemorate and love their prototype.”

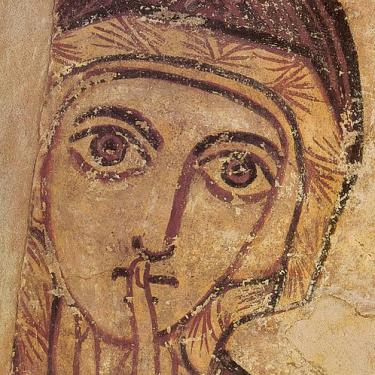

With this in mind, let us consider this image of St Anne, mother of the Theotokos, an 8th- or 9th-century fresco which was discovered in the excavation of the Faras Cathedral in what used to be called Nubia, present-day Sudan.

The expedition was led by Professor Kazimierz Michałowski in the 1960s as part of a UNESCO project to preserve relics from the medieval Nubian kingdom, which once ruled the Nile Valley.

Christianity was practiced by people in Nubia in the first century and grew in influence during the Byzantine Empire. During the reign of Emperor Justinian, Nubia became an important Christian center. In 580, Christianity became the official religion.

St. Anne was venerated in ancient Nubia, and it’s believed that women would pray to her asking her help in conceiving and giving birth to a child.

Let’s take a closer look. The strong lines of her face form a powerful graphic image: clear, bold lines, unadorned. She has an oval face and two enormous eyes looking just past us. They are wide, focused on some vital yet mysterious thought. Her dark, heavy eyebrows and the strong shaded line of her nose frame her brown eyes which are wide open. Her head is covered in a brown hood that has a decorative pattern around her face. Her hand is raised to her mouth with one, long delicate finger touching her closed lips.

It’s an amazing image. What is she thinking? What does she want us to know? Is it a secret? Is she protecting someone or warning us to be silent?

According to some scholars, the gesture, which is rarely seen in Western art, may refer to an Egyptian Christian (Coptic) tradition in which people prayed quietly while holding a finger of the right hand on one’s lips. The gesture protects people from the evil that would try to enter the human heart during prayer.

I could watch her forever. The image presents us with a major esthetic and spiritual encounter which brings us to ask, What is the intersection between the human creativity in this drawing and holiness that it evokes? We see art here as traces of the holy. It points to another dimension beyond the deceptively simple traces of marks on a wall. To me it brings a sense of humility. What I’m seeing is bigger than me, yet I am not diminished. I feel an invitation. I want to know what she saying. If I could just look long enough and open my heart maybe I would know. Her message seems urgent. Here she is from Africa, Sudan, 1400 years ago--and yet very present.

The image for me rules out the stark dualism between the material and the spiritual, at least enough to assert that the material is not lower than spirit. After all, thinkers from Plato to Einstein assert that we think in images. Our experience with an image like this provokes intellectual, emotional, spiritual, as well as tactile pleasure. And the Orthodox Church maintains this mystery, it does not overdefine physical versus spiritual, but invites us to experience both in worship.

I started this journey into her life and what it means to the church with this icon, caught up in that intriguing glance to find a way to learn about her, to spend time with her and see how she can lead me to a new place in my prayer life.

Judith Scott is Axia's spiritual advisor.