On Gregorian calendar Good Friday this year, our blogger and board member Judith was invited to give a talk at a friend’s church about the second of the “Seven Last Words of Jesus. The icon you see here that she refers to is Ethiopian, from the Alamy collection.

Seven last words: “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

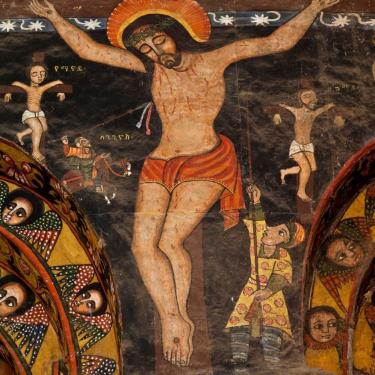

I’d like to begin this meditation showing an icon from the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Seeing this icon from Ethiopia, we affirm the ancient Christian religion, birthed and shaped in Africa. It gives us time to rest a while with the sacredness and emotions of the Crucifixion.

Let’s take a look. First we see the central figure of Jesus. He is hanging, suspended from the Cross.

On our left, the figure near the top margin is Mary, his mother. On our right, the beloved disciple. (We read in Scripture that the other women, Magdalen, and the others are there, but all of his male disciples and friends have fled.)

Under his left and right elbows are the thieves.

And below them are the soldiers, one piercing his side with a sword, the other offering a sponge soaked in vinegar.

Around him are angels, depicted in the Ethiopian tradition, God’s messengers, heavenly host, present yet invisible.

The image is stylized. Not real like a photograph. There is no real background, as if this floating in space. It’s as though this is a dream of the Crucifixion, lifted from reality because it was too real, beyond our ability to really comprehend. It is outside of time and space.

But we feel the emotions. See Jesus, body slumped, eyes closed, head to the side; Mary and the disciples, eyes wide, hands clasped in prayer; the soldiers arms lifted up, strong movements directed at Jesus; and the angels looking down on everyone and everything, concerned. How must we all look from Heaven?

And now for those thieves. We know that Jesus is being mocked, taunted, ridiculed. He’s been whipped and tortured, his hands and feet nailed to the cross. He’s been paraded through the streets, where people spat on him and jeered: This man is no king, they yelled. He has no power. And we know he is dying.

One of the robbers taunts Jesus, but the one on his right stops this miscreant. “We belong here,” he says. ”But this man did nothing wrong.” Then he calls to Jesus: “Remember me when you get into your kingdom.“

And Jesus replies with the second of the last words: “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

Through his pain, in the throes of death, Jesus responds with compassion, offering hope and salvation to a criminal, an outcast who turns to him, turns to God.

Why are we asked to look on this scene? Why are we asked to subject ourselves to the pain and horror of his death? It’s a public execution, carried out by imperial powers who care nothing for Jesus and his people, who need to exert their sovereignty, to publicly proclaim that this is the fate that awaits anyone who disrupts or disturbs the Empire’s ongoing rule, its day-to-dayness, its business of oppression, greed, and military might.

Why did Jesus have to die this humiliating death, and why does the Church ask us to witness this brutality, this agonizing death?

I went to seminary, and we read many theologians from the earliest days of Christianity up till now. We learned that Jesus the man died, but not Jesus the Divine Son of God. We learned that Jesus died for us, for our sins, and we have to remember that. We learned that, when we look on the Crucifixion, we are facing ourselves, our deepest darkness, but that God is there too: God’s mercy and God’s promise are there with Jesus.

And we learn that God chose to be with the poor, with the powerless. As Rowan Williams says: “Those in the extremity of hopelessness, with nothing to say that power can hear. The silenced, those outside the gates.”

Yes, these theologians and we students, studied Scripture. We examined the liturgy and prayers and hymns, and the lives of the saints. It was the theology of the Ivory Tower. The academics, philosophers, writing their books and talking to each other.

But this year, the theology did not comfort me or satisfy my need to know—- deeply, spiritually—- what was happening on the Cross? What are we called to see and understand? What meaning does this death have for us in the year of our Lord 2021?

I was distressed, disturbed, deeply troubled. And it came to me. I was watching the trial of a police officer who had deliberately and callously drained the life of a man, in full view of the public, on a sunny spring evening. The man he killed was Black, the neighborhood a poor one in a major US city. The witnesses were testifying, in their words, from their videos. They had seen a public execution by an agent of the state, a white police officer. They had heard the black man’s last words, gasping and pleading for mercy. From their trauma and their humanity and their powerful need to make sense of the senseless and to make themselves heard, they had something to teach us, to tell us, about this 21st-century Passion story.

One of my most distinguished professors, Rev. Dr. James Cone, taught us that there is the theology of the people, the theology of the churches, where people do their own thinking about God and make meaning from life’s experiences. There is tradition in this that is its own theological text. It is the genius of the Black Church, created and witnessed in the worship of the people. Another distinguished professor, Vincent Wimbush, taught us that Scripture--that is, the texts inspired by God and worthy of our attention--is written today, by the people, living their lives in whatever circumstances they are in. This is the theology of the streets, making our words sacred, and our lives sacred. Their words are our text.

George Floyd was not Jesus. He was a man. He WAS a man, made in God’s image, murdered before us, and dying as the man Jesus died on the Cross. He called out, too, “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe,” 17 times. He called for his Mama, as Jesus called for his Father and spoke to his mother. And the words of those who witnessed George Floyd’s death express the strong identification they had with this dying man, the raw emotion and grief they felt. It is the stuff of hymns and prayers of the Church that we sing and pray on Good Friday. This is Lament.

The bystander Mr. Milian wept on the stand when he recounted Mr. Floyd’s words. “He called for his Mama,” Mr. Milian said. “I know what that feels like because I lost my mother.“ Court had to go into recess. Do you hear the echo from Jesus last words?

The clerk, 19 years old: “I felt disbelief and guilt. I could have just took the bill.” Do you hear yourself asking: what wrongs have I done, what sins that led to this?

The firefighter, 27 years old: “I would have checked his airway. I would have been worried about a spinal cord injury because he had so much weight on his neck. I would have opened his airway to check if there are any obstructions, and I would have checked for a pulse," she told the court. Hear our own helplessness, our impotence in the face of this tragedy.

"The cop" had a "cold" and “heartless” look in his eyes, Mr. Williams, 33, an MMA athlete said. “He didn’t hear me.”

“I literally watched police officers not take a pulse and not doing anything to save a man. I am a first responder.” They pushed her away.

“There's been nights I stayed up apologizing and apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more and not physically interacting and not saving his life,” said the 17-year-old young woman who took the video.

They were powerless. Unable to act. Hear that. They had nothing to say that power can hear.

She continued, “But it’s like not what I should have done, it’s what he should have done.” INDEED.

She said: “When I look at George Floyd, I look at my dad. I look at my brothers. I look at my cousins, my uncles because they are all Black," she told the court. "And I look at how that could have been one of them.” We are in God’s image. Jesus was one of us. George Floyd is one of us. We are all children of God.

And now a chorus of voices from the testimony.

I believe I witnessed a murder.

I saw a murder.

I literally have it on video camera. I just happened to be on a walk. This dude ― this ― they f….g killed him.”

Did you ever see anyone die? It’s upsetting.

What we saw was the anguish of the witnesses. The truth they perceived and spoke…. No this is not official, sanctioned police action. They called it as they saw it. “This is a murder,” they claimed.

And we could see and feel their grief, their outrage, their trauma.

And now I know why the Church has us look at the Crucifixion. So we see ourselves in Jesus and Jesus in us. So we understand that this is not another day. Another one of the thousands of executions that happened then and now. Jesus paid the price. Jesus—-God—- is there on the Cross. He died. I can’t let this go. This must be remembered. He must be remembered.

And we all bear some guilt, because we have known how murderous this country is for Black people for a very long time. Have we done enough?

We are left to pick up our cross. To speak up. As these witnesses did.

Jorgen Moltman wrote: Jesus is wherever crucified people are in the world, where every day there is a crucifixion, Jesus is there.

As the Crucifixion and its message has spread across the world with its depiction of horror and injustice, so has the death of George Floyd and its recording. It has reverberated around the world with protests and calls for equality and the end to state-sponsored terrorism.

The crucifixion was more than one man on a cross… it affected Creation itself. Liturgist wrote these words for the Orthodox prayer services of Holy Week:

Beholding You, the Fashioner and Creator of all, hanging naked on the Cross,

all creation was changed with fear and lamented.

The sun withdrew its light, and the earth quaked;

the rocks were rent, and the splendor of the Temple was torn asunder.

… the hosts of angels were amazed, saying:

“Oh, the wonder!

The Judge is judged and suffers,

desiring this for the salvation and renewal of the world.”

From community activist Toussaint Morrison: “It has people in a liminal space. It feels like the environment is holding its breath. The gravity is a little heavier. The sun is a little brighter. The wind blows a little bit harder. The cars move a little bit faster. There’s a sense of urgency for something that nobody can control. The trial is weighing on the entire city, and especially the square.”

I hope and trust and believe that angels surrounded George Floyd as he died in his unlawful murder, this 2021 lynching. I hope and trust and believe that he heard the promise of Jesus, “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

Judith Scott holds a masters in theology from Union Theological Seminary.