The morning of September 11, 2001, saw a cataclysmic event claim thousands of lives when the shocking impact of airplanes flying into the Twin Towers created a hellish nightmare of flames and falling debris. Then came the sudden collapse of the buildings, a sinking of concrete and steel, roaring sounds, earthshaking tremors, and plumes of smoke that covered lower Manhattan. Destroyed in the collapse that day were the archive offices of two New York City archeological sites dedicated to uncovering the lives and experiences of people who lived in New York centuries ago, people who helped build the city to international prominence and whose lives were forgotten and distorted. The African Burial Ground, discovered during construction near City Hall in 1991, revealed the remains and burial artifacts of African-American people, most of whom lived as enslaved laborers and servants, dating from the early 1600s. Another discovery in 1991, not far away beneath a parking lot in Lower Manhattan, revealed an array of artifacts: personal and household articles, craft and business tools, and commercial objects from the nineteenth-century Five Points neighborhood, a densely populated area of new immigrants--a notorious slum.

Archeological and forensic examinations told stories that changed the way the city tells its history and shatters images of the city’s people. The African Burial Ground was proof that black people lived in NYC from the beginning of European settlement here. The bones showed signs of harrowing injuries, bodies distorted from repeated labor: carrying, dredging, and loading heavy objects, continuous wear and tear from close handwork, and stress injuries from repeated actions. Many remains were those of children who had died from crushing blows. Nutritional study revealed dietary deficiencies, and biologists found signs of death from plagues like tuberculosis. Alongside the skeletons were cultural artifacts like beads, rings, buttons, and shroud pins attesting to religious and cultural echoes from Africa and New World practices and beliefs, testaments to survival in brutal conditions and the creative, spiritual strength and cultural flourishing that refused to be obliterated by inhuman condition of chattel slavery.

The Five Points had a reputation for criminality and licentiousness: brothels and bars, drugs and human trafficking. The tabloids of the day published lurid accounts of uncivil behaviors and squalid conditions. Archeologists found over 850,000 items used in everyday life: “soda bottles, tea sets, thimbles and inkwells.” Some of the items were endearing: a child's porcelain teacup, children's marbles, clay pipes, one carved with the head from classical Greek or Roman mythology. There were “scraps of cloth from home businesses, ornamental hair combs, tea cups with messages urging little boys to be good.” “What does it mean,” one archeologist asked, ”that these people (largely German and Irish immigrants) who were supposed to be down and out criminals, were setting their tables with matching dishes and supplying their children with toys just like the middle class.” Their lives had been willfully misinterpreted to stoke fear and disdain against immigrants and the poor.*

What happened to the archives? The human remains from the African Burial Ground had been sent from Six World Trade Center to Howard University and a hundred boxes--almost the complete collection of artifacts--were found after the debris had been cleared. But the Five Points collection had only paper records left in the wreckage. All of the objects, which had been carefully cleaned, studied, analyzed, and documented, were gone. Until collection officials remembered that the Archdiocese of New York had borrowed 18 of the most precious artifacts, which were now safe.

I read this story while preparing for the Exaltation of the Cross, the day that every parish sees the Cross raised by the priest, lifted in four directions for all the world to see, as he chants “Lord have mercy” repeatedly and the congregation performs our prostrations. We sing “Before thy Cross we bow down in worship, O Master, and thy Holy Resurrection, we glorify.” The Cross is the site of Christianity’s most sacred and powerful mysteries. Jesus on the Cross, the humiliation of the World and the Glory of the Lord who is released from this world and proceeds to conquer death for all of us, now and forever more. It is not just a symbol. The true cross is the material evidence that Jesus was crucified, that he died for us, that the world can see the truth. When Emperor Constantine sent his mother Helen on her search, they knew what they were looking for. It would not be a surprise but confirmation. And the people with her had to dig at the urging of an old man who kept the memory of the site from stories told to him through the generations. Rome had built a pagan temple over the site to erase Christian memory. And, when found, it needed to be verified. It was. A woman was cured of a terminal illness when she touched it. A person who had died came to life as his bier passed by.

The true Cross is not just a wooden object. The excitement and ebullience the archeologists feel at the excavation of things from the past, the inspiration that fuels the careful analysis and eventual exhibition of their finds, comes from the connection to lives past; the centuries-old thread of human existence and achievement that binds us to a common humanity; the thrill that hands like ours crafted and molded and held these materials. That is the history of people.

Tia Miles writes in her book All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley's Sack, a Black Family Keepsake, "Things become bearers of memory and information, especially when enhanced by stories that expand their capacity to carry meaning. …" Jane Bennett developed this difference between a found object and a thing by pointing to the strange vitality of the thing in relation to human experience and specifying that an object transforms into a thing “when the subject experiences the object as uncanny.”

The meaning of the Cross goes beyond this as a relic of human history with cosmic significance. We know every year that our parish Cross is a crafted icon, a stand-in for the real thing. But its power is awesome. Our litany brings us to experience with exuberance and humility the death of Jesus and the promise of renewed life. We remember the price that was paid and what we inherit.

The archeologist Rebecca Yamin said, “The record of the past being lost is always a tragedy. It’s not the same as the tragedy of human lives. But it’s a loss of understanding of who we are and where we came from.”*

And so the search for the True Cross was inspired by the spirit and energy behind our liturgical and evangelical quest to remember our foundation story, the miracle of the life and death and resurrection of Jesus, understanding who we are and where we came from as Christians.

Judith Scott is Axia Women's Spiritual Director. She holds a masters in theology from Union Theological Seminary in NYC.

The icon of the Exaltation of the Cross comes from 19th-century Russian.

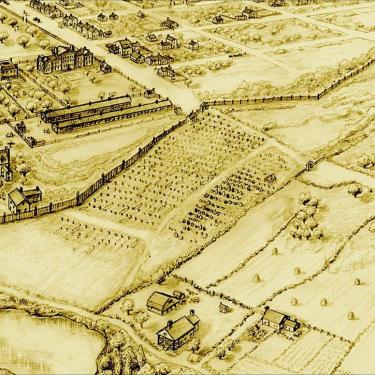

The photo, by Patti McConville, shows part of the excavation of the African Burial Ground and indicates the estimated age and sex of those who were buried there (1630s to 1795).