My father was born and raised in rural South Carolina in the Jim Crow South post World War I. He was part of a large, close-knit family in an established community of workers and farmers and teachers and preachers, business people and entrepreneurs. My father was a great storyteller and he told us how he and his brothers, friends, and cousins would go deer hunting every year. One day, when he was a young man, he went into the woods and saw a beautiful deer. He raised his rifle and aimed it. The deer turned and looked right at him. My father said they looked at each other, without moving, for a long moment. “I put the gun down,” my father said, “and I never went hunting again.” My father’s name was Ulysses.

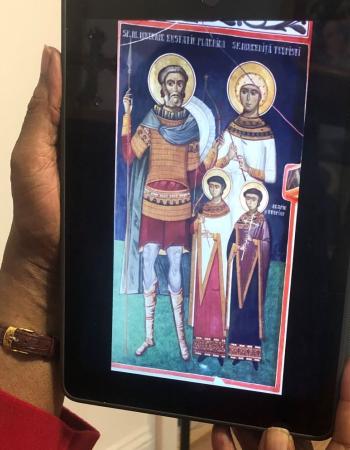

So when I read the story of St Eustathius, I was struck by the same story. Ulysses and Eustathius each had an encounter with a majestic creature, and saw into the soul of a living being, sentient and whole, a creature that was part of God’s creation the same way they were. For each of them, it was an opening to another world, a space beyond ours, where animals are living and knowing and free. It was a moment of revelation, a life-changing moment.

My father never lifted a gun to a living creature after that.

St Eustathius saw the Cross of Jesus and heard the voice of God calling from the deer, "Placidus," which was the saint’s former name, "wherefore followest me hither? I am appeared to thee in this beast for the grace of thee. I am Jesus Christ, [and] I come hither so that by this hart that thou huntest I may hunt thee.... I am Jesus Christ who appeared on earth in flesh for the health of the lineage human, who was crucified, dead, buried, and arose the third day."

Just am my father never hunted again or took a life, Eustathius gave up his old gods. He embraced Christianity and he and his whole whole family were baptized.

This story for me travels across time and space. It is the resonant echo of sacred revelation.

But both Eustathius and Ulysses had to return to the world. We all do. And while we may carry a moment like this within us, the world takes its inevitable toll.

After their baptism Eustathius, his wife, and two children were captured and separated from each other. Eustathius himself was held captive as a slave in a distant land. Like Job, who was devoted and obedient to God yet lost his wife, children, land, and herds of animals, everything was taken from Eustathius.

For each of them, it was a time of intense suffering. Job’s friends try to help him find meaning in what has happened to him, to comfort him. They argue that Job must be being punished for his sins. Their arguments are shallow, hollow, irrelevant, and ultimately not true.

But Job and Eustathius through devastation hold on to God. They each say: “The Lord gave and the Lord took away. As the Lord willed, so has it been.”

Job’s family and land are eventually restored. Eustathius is freed and reunited with his family, but they are finally martyred declaring their firm and constant faith in Jesus.

What are we to make of this? Really. You are an ardent believer in the Lord of Justice and Mercy, you stay faithful in your ways, and then horror comes to you? Horror?

We are close friends with a young woman. She is exuberant, professional, a partner in the happiest marriage, still under the spell of love and filled with surprising joy. Their baby is 16 months old. Early Friday morning last week her husband woke up, saying, “My chest hurts.” Then he died. He was 34 years old.

At the outdoor viewing on a sunny day near a beautiful lake, the funeral guests, well- meaning people, family, and friends, good Christian people said: “This is God’s will” and “He’s in a better place” and “God called him back home.”

I watched my friend, tears flowing down her face, yet stoic and rigid. Breaking the protocol of social distancing but caught up in a moment of unimaginable grief, we embraced. “You must be so angry” I said.

“I am,” she answered. And pointed heavenward

She was shaking, in shock, and there it was. Rage. Rage, shock and bewilderment. “You can be angry at God.,” I told her. I was thinking of Job, Eustathius, and all the Old Testament prophets who yelled at God and challenged him. Even Jesus at the end of his time on the Cross called out, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?”

I turn to today’s Epistle and the words of Paul: "We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus…"

How could he do that? I think, Is that what we should feel? Is this even possible?

And again: "We who are alive are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that his life may also be revealed in our mortal body. So then, death is at work in us, but life is at work in you."

As Jesus exhorts us to take up the Cross, we recognize the dread burden this is. The energy and fortitude it takes. The real message may be that Christianity is not for the faint of heart. Things can get real, real fast. And that’s where Jesus is waiting for us. To be there with us and help us through.

“Don’t sing songs to a broken heart,” the psalm advises us.

So what do we do, for our friends, for ourselves?

When my father was in hospice care, the nuns asked, "Do you want us to pray with you, Mr Scott?”

“No,” he said.

My mother, as she was dying, said, “ No hymns, no singing.”

My friend does not want to hear words about God.

What happened? What did they lose? Certainly they were loving people. They loved and were loved their entire lives. I was worried. And I felt great sorrow. But it is all right. They are not alone. We and all the saints pray for them.

We pray as Evagrius tells us to. We pray with strength and fervor. Evagrius called prayer a direct, ongoing, interaction, a spiritual intercourse with God. And if our friends and family can’t pray, we pray for them. And we must be mindful of the words. Say the words: "Our Father who art in Heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in Heaven…"

And:

"Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me."

And:

"By the prayers of the Theotokos, O Savior, save us."

Each prayer is a plea, a reaching out. In African-American culture, the people say, "Lord have mercy!!!"

Maybe what Paul writes is not a description, but an aspiration, an encouragement for us: "For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord."

It’s not we alone who will not separate from Jesus Christ, but God, Jesus Christ, who will not separate from us.

These words, too, resonate through the ages: the words of faith, of lamentation, words of prayer that reach out to God, that resonate as echoes. The practice of prayer—-alone and in community—-to hold up those who are in despair is an ancient discipline and encouragement . And we, as Orthodox, never pray alone. For when we pray, the entire witness of the saints prays with us.

So we must pray. We must build community and pray and work together—-which makes Zoom meetings so very special to me now. And we must take the time, especially in the isolation and uncertainty of these days, to take a moment, to look deeply into the eyes of our fellow creatures—-two legs and four—-and find again the majesty and awesomeness of God’s presence.

Judith Scott is a frequent blogger for Axia Women. She holds a master's in theology from Union Theological Seminary in NYC.